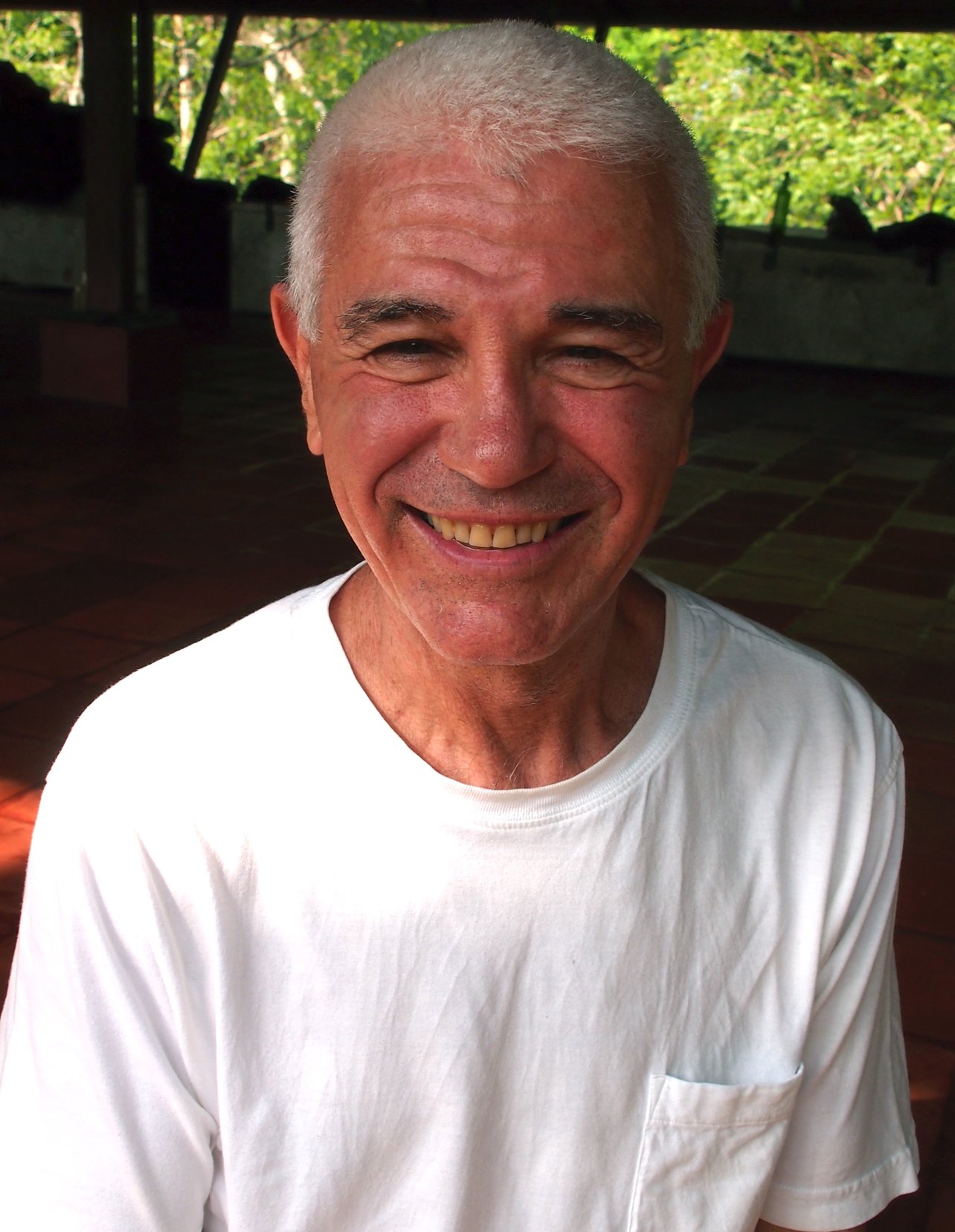

MARTIN MOSKO

The garden is the source.

Buddha was born in a garden,

reached enlightenment in a garden

and died in a garden.

Adam and Eve were born in a Garden,

and ever since they ate from the tree

of wisdom, we have been longing and

searching for the return to the garden.

I’ve had many interests and pursuits in my life. It has often given me pause to see how all these seemingly different parts of my life meld together and inform one another, each improving each.

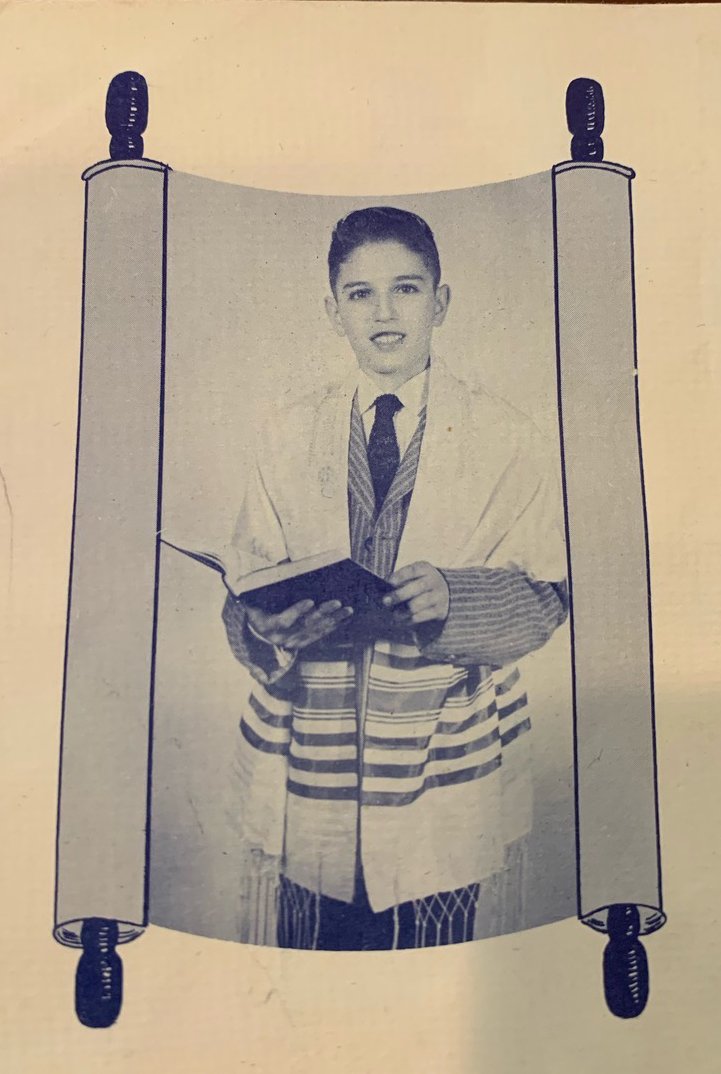

I was born in Denver, Colorado, no longer a frontier in the traditional sense, but certainly one in the sense that there was no particularly dominant culture or aesthetic. I felt free to explore spiritually and artistically, which has informed all aspects of my life. I grew up in a nominally Jewish family and became interested in the religion as I prepared for my Bar Mitzvah. I joined a study group with our rabbi and aspired to become a cantor (the one who chants the rituals). But I had other interests and influences: I began meditating and doing yoga at about the same time, exploring ideas of Eastern religions about which there was very little written in English at the time. When I took a break from Yale University to join the Peace Corps in 1965, I wouldn’t have called myself a member of any particular religion. In India, I was immersed in a different culture and a different spiritual understanding, and became interested in Buddhism. When I returned to finish my degree from Yale, I changed my major to the study of language so that I could read the Vedas in the original Sanskrit.

Part of my Peace Corps training was to find a project that the entire community I was in could support. After speaking to most people in my small village, about the only thing they all agreed on was that they could use a park, which led me to design and build my first garden there. Later, after finishing my degree at Yale, my partner (later wife) Sabine and I went to Martinique, to await the birth of our first child. There we lived in a little house near the home of the bishop, and I trained with the gardener for the cathedral, extending my understanding of design and maintenance. Though I cycled through a number of jobs as I moved around the U.S. with my family to pursue my spiritual understanding, I eventually came back to gardening when we settled in Boulder, Colorado. I incorporated my company, Marpa Landscaping, named for a great adept and farmer in 11th Century Tibet, bought an elderly truck and a wheelbarrow, and opened shop. From that small beginning grew my career in making gardens.

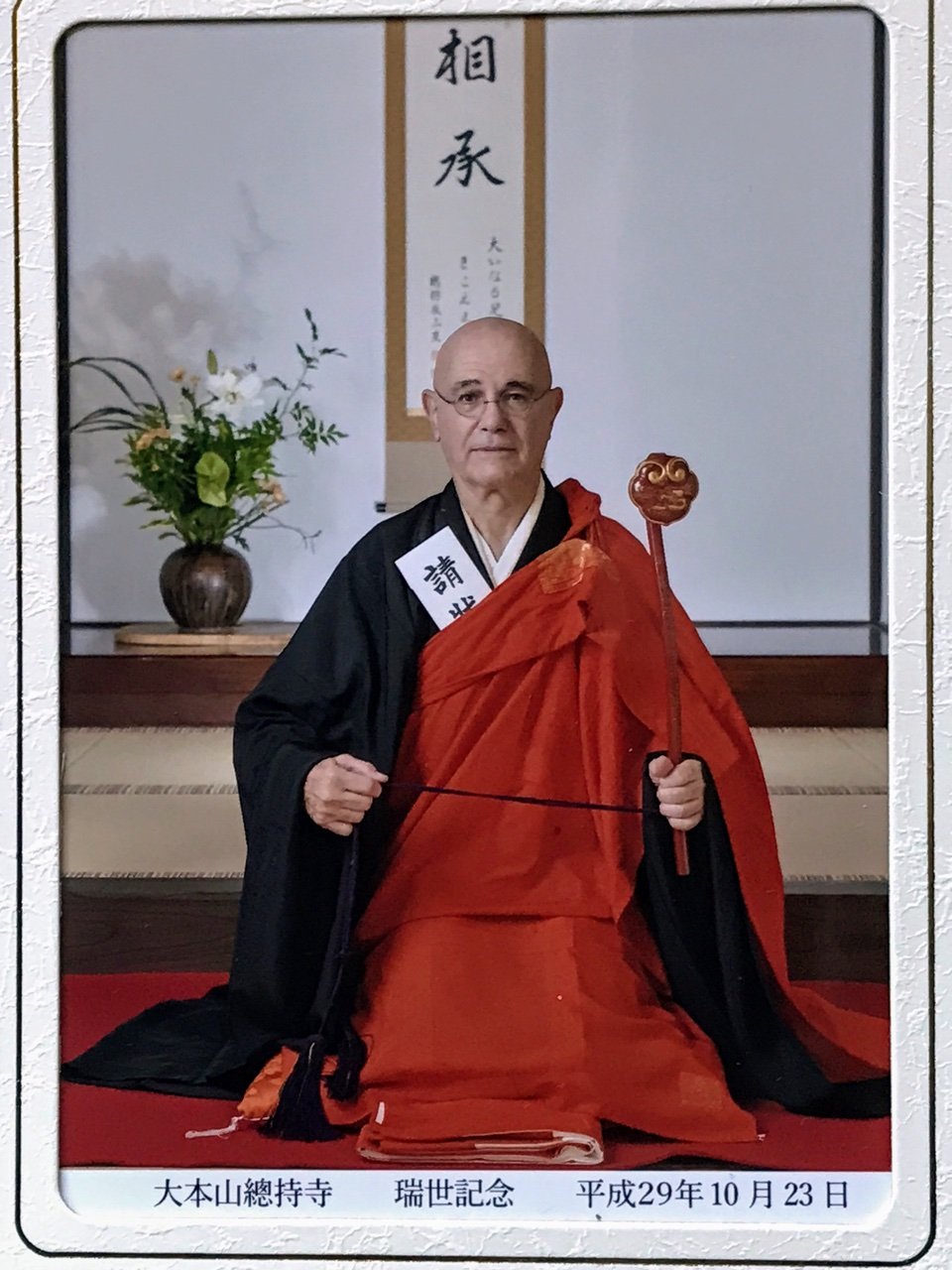

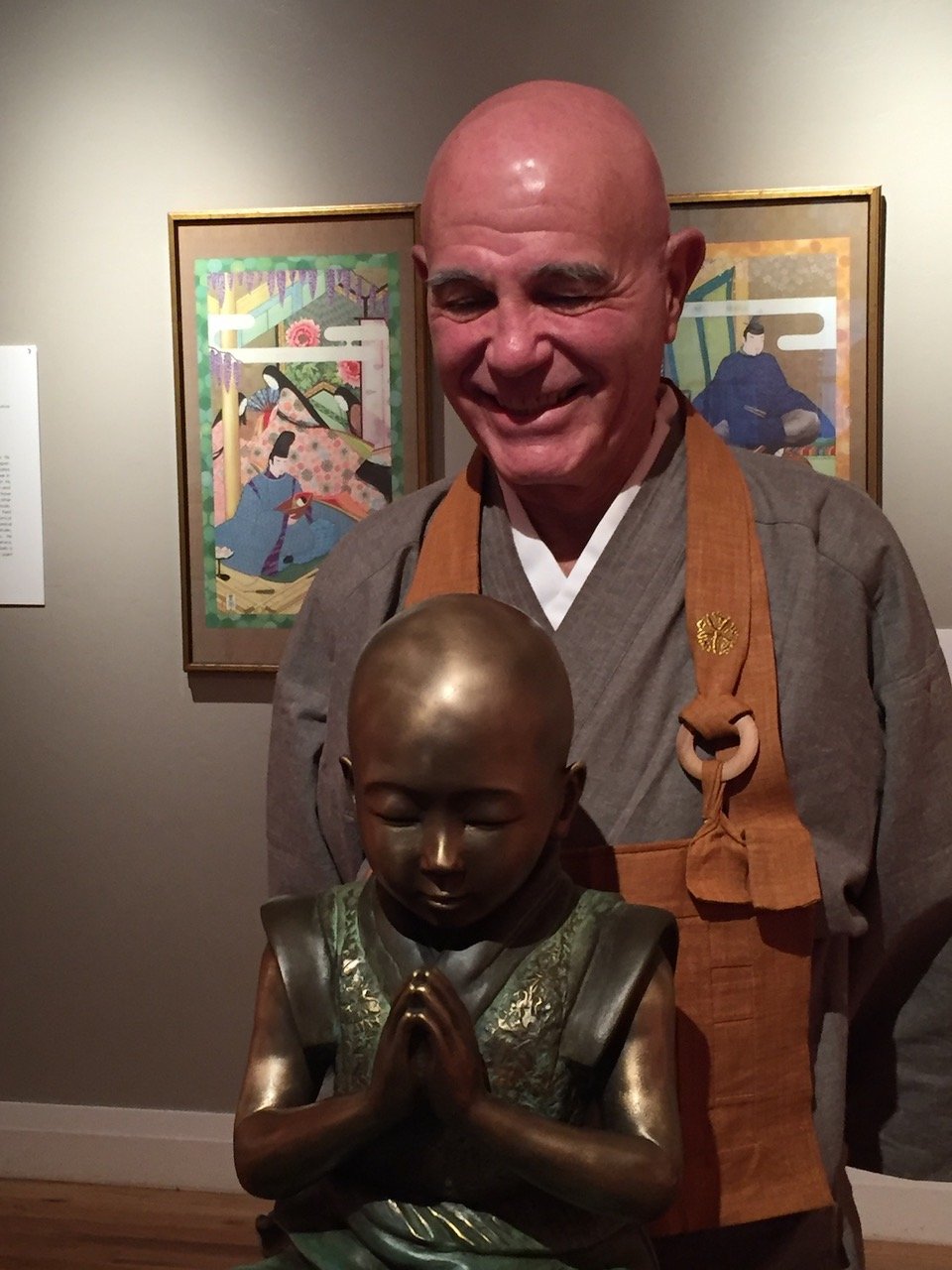

This has been the way of my life: my spiritual explorations lead me to certain places to study, and in those places I’ve built gardens. I take lessons from the gardens that lead me onward to different spiritual directions. Now I could say that either I’m a monk who makes gardens, or a gardener who happens to be a monk, and both are true.

As adding new colors of yarn enhances a woven cloth, my other interests have brought more insight to both my gardens and my spiritual practice. I have always created art, and the step into photography came when I treated myself to a good camera after a particularly financially successful year in garden design. I used it to take photos of my gardens and of nature, and from behind the camera lens I learned to see more carefully, to explore what makes our environment look and feel a certain way. The textures of tree bark, the varying heights of plants, the placement of stones, the way a path wends through a landscape: they all work to produce an experience that goes beyond these particulars; they create more than the sum of parts. Photography helped to bring the principle of the “mandala” into clearer focus for me, and enhanced both my ability to create sacred spaces and to see them in my mind.

Structural integration (taught by Ida Rolf) became an interest after a palm reader in Thailand told me I should learn how to work with the human body. I started by studying massage, then attended the Guild of Structural Integration, learning how we create our own forms, our own mandalas, out of our life experiences. Trauma and injury narrow our minds and pinch our bodies into unbalanced shapes, where freedom and openness lead to a greater harmony within the body. I understood more about the relationship between body, mind, and environment—which again led me to interesting ideas for gardens, and to greater spiritual insight.

Becoming a father and a husband brought me moments of anguish and fear for the well-being of my family, but in that I have learned to open my heart to others in a way not possible to a hermit. I was driving one day soon after I had my first child, and suddenly realized why insurance companies would reduce premiums for parents: we drive more carefully when we have responsibilities to our children. I learned how important it is to support all other beings more than myself. This insight eventually led me to taking monk’s vows.

I’ve learned from my clients the importance of relationships to design. When the relationship with the client went well, so did the garden. If the relationships among the work crews were good, so were the gardens. Our interconnections are crucial to creating something both beneficial and beautiful, and those lessons have extended throughout my life.